Applying Elastic Leadership

So we learned about the Elastic Leadership concepts and saw the process in a nutshell. Now you might ask, "Ruben, how do we apply Elastic Leadership? How do we actually implement it?"

That's a great question! Let's have a look at:

- What can we do to get out of the survival mode? As you might remember, in survival mode we (as a team) don't have any time to learn and try new things. The good news is that to get out of this mode it's easier than it sounds. The bad news is that you might not like the methods.

- How do we make sure that the team learns? The learning stage is a tricky one, are you and your team going to be as efficient as before? Probably not. We need to manage expectations and make a learning plan.

Getting out of Survival Mode

Why are we in this situation in the first place? The first thing is to understand that we're in a so called "survival mode" because of our own doing. Wether it's because we were hired to do this job and got the responsibility to support the team (No one hires if they don't have a problem) or because our previous decisions and team habits led us here.

The good news is that since we are responsible for our decisions, we can also take responsibility to get out of this situation.

From the book and my experience we can apply the following techniques:

- Find out what we've committed to: We need to first make a map of what we've already planned to do.

- Renegotiate our previous commitments: We need to check what's top priority and what can be postponed. Our priority here is to make a plan for the next 2 months, which can be done. Once it's finished, we can have a larger slack time for the team to learn.

- Collect Risks: We can't plan for something without clearly understanding the risks we currently have. What could go wrong in the following 6 months? What happens if we get rid of certain commitments? What are the possible consequences of our plan?

Mapping the problem

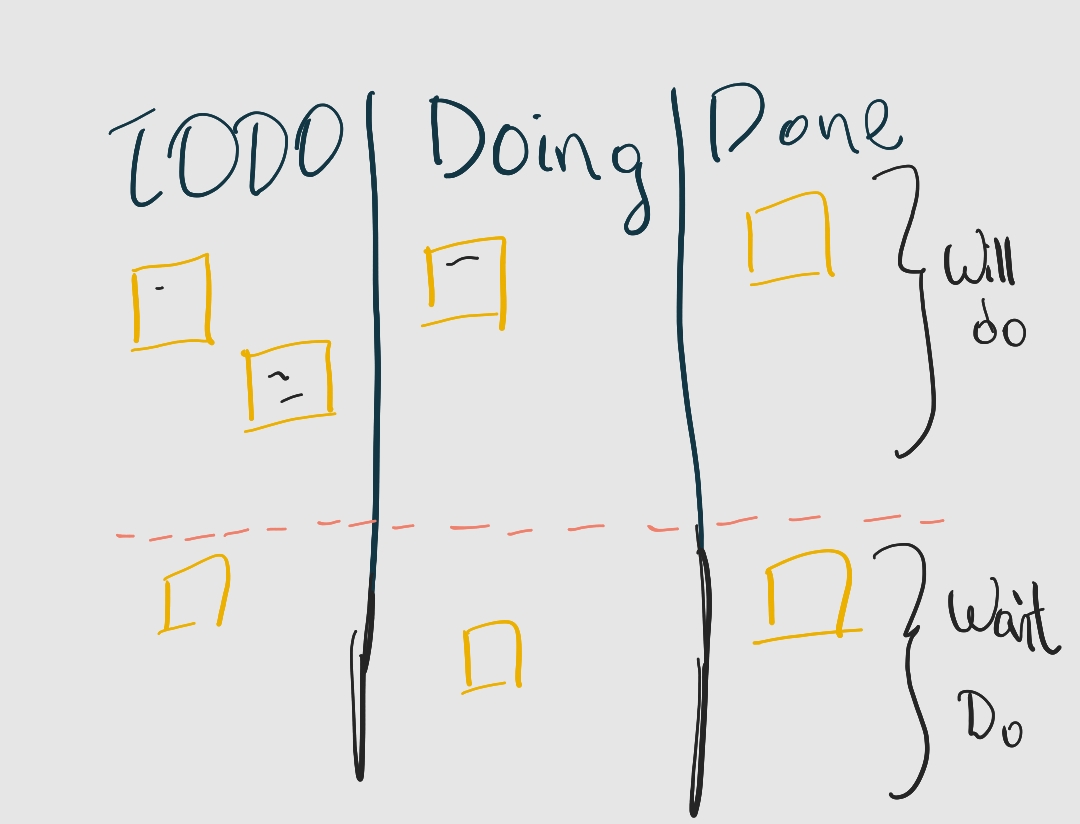

The first step to solving the issue is to observe it and clearly define it so everyone involved can understand it. If you're using a project management solution (like Jira or Trello), then the job is almost done. You can look at every epic and story committed for the quarter and bring it to a whiteboard (virtual or real).

If you use a more manual approach it makes sense to bring the team (doesn't have to be the whole team) and stakeholders to collect every requirement. What are the deadlines we've committed? What's the priority on our commitments? What happens if we postpone?

Check dependencies: what can we really control and do, where are the dependencies? Are we waiting for a team to finish something?

Another question that we need to ask for our commitments is: what exactly is busy work and what's essential? Maybe some stakeholders don't care much about a particular feature, or it's just a nice-to-have. Maybe we're focusing too much on a technical debt that isn't urgently required (check for 2.0 in the name of the epic) or there are features that are not clearly defined or that we don't know how to solve clearly.

Once we have everything on the whiteboard, we need to check realistically what can be done in 2 months. What's the velocity of the team? If it's an average of 12 story points per sprint or you're finishing 6 stories per sprint, chances are that it's going to stay like that with small variations. If you're not learning there won't be any miracles; what you see is what you get.

The next step is the most liberating one, you check what can be realistically done by the team in 2 month and make a red line: this will be done, and this won't be done.

Renegotiate our commitments

With our action plan, we can start renegotiating our commitments with our stakeholders and upper management.

Here be dragons. Many people get discouraged by uncomfortable discussions, but you (my dear reader) are not one of those persons. Introducing changes and solving the problem at its root takes a lot of courage. As we mentioned before, we are in "survival mode" because of our previous habits, and changing habits is not easy. Being in survival mode is our comfort zone, and we need to get out of it if we want to improve.

Will your stakeholders take the news easily? Maybe not. Will you lose face? The chances are not 0%, but if you're in a position where you can help improve the team and the overall environment of the organization, aren't you going to take it? Weren't you hired to lead? This is what leaders do. It's not about having a cool title on your LinkedIn profile; you have to solve problems.

How do we approach this conversation? The good thing is that we already made a plan with the team's capacity for the next 2 months. Ideally, you can collaborate with your stakeholders to check what fits into the 2 months and what can be removed. If you're working on a whiteboard or with sticky notes, the process can be very visual: if you add features into the planned 2 months, some other feature or story needs to be removed.

Collect Risks

You know what they say: "Man plans and God laughs." No plan is perfect, and we're probably going to deviate from it at some point. But without plans, we can't reach any goals. Therefore, we need to make sure we collect every blind spot in the team.

If we follow the plan as it is, what could go wrong? Is there something we're missing?

In the book, Roy Osherove recommends facilitating a risk collection meeting with the following premise:

6 months from now, and the project has failed completely. Why did it fail?

This is what we call a futurespective.

In the meeting, the team will brainstorm on what could go wrong, and you'll be able to collect more feedback for the plan. Afterwards, you can prepare accordingly.

So... where's the command and control?

As I previously mentioned, in the survival mode we maintain a command and control leadership style, but what we've read so far is mostly collaborating and planning, so what gives?

In our day-to-day basis we need to focus in our current goal: get out of survival mode. Therefore, we can't waste time discussing and researching for best practices and solutions, we need to do.

Let people maintain their expertise and solve the problems they already know how to solve. If you're technical, be with the team and develop shoulder-to-shoulder. You've proposed this plan, and you need to follow it as well. There are no exceptions.

Learning how to Learn

After we implement our 2-month plan, we should have enough slack time to learn as a team.

The first question I get asked when I mention learning time for the team is:

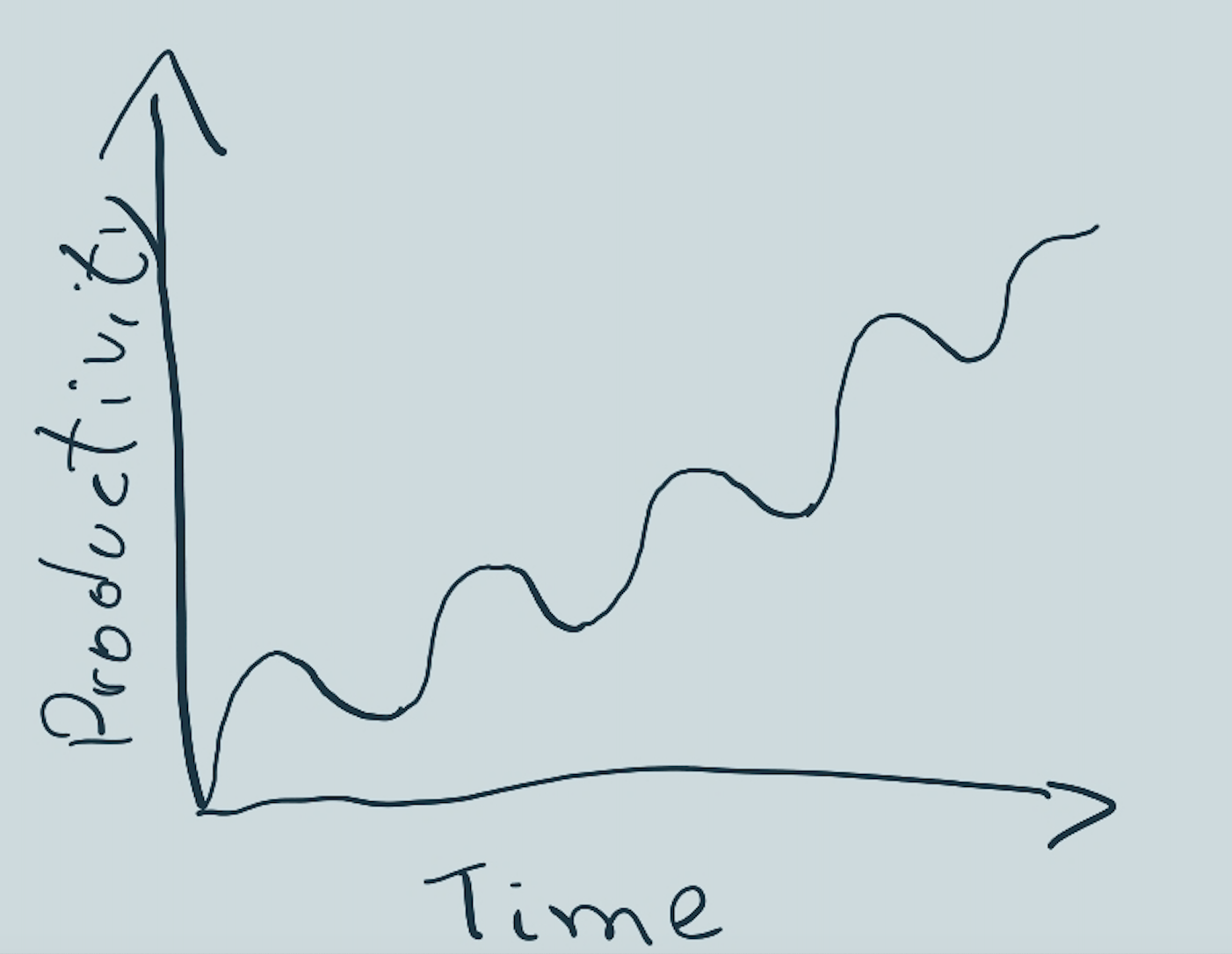

How does the team capacity and performance will be affected by the investment in learning?

In general, we should allocate around 40% to 60% of the team's capacity to learning mode. This means, if the team is finishing 100 story points per sprint, it will take on around 40 to 60 story points during this period.

The second question I get is:

Can't the team be bold and just work with the same number of tickets while learning?

It generally takes 10x more effort to learn and do something new. If we also consider the effort from pairing and working together as a team to ensure knowledge sharing, we understand that halving our efforts to learn is already bold enough.

Why do we even do this?

When we're learning, we realize at the beginning that we're not as fast as we were before. This is normal. The idea is to find new ways of solving problems so we can add them to our mind toolbox. If we just keep doing the same things, we're going to stagnate at a local optimum—a point where we work fine but can still improve.

If you've ever learned an instrument, you probably remember times when you had to learn a new technique: you study and practice the same thing over and over until you get it right.

(Same bass player, same technique)

Monitoring

It's very important to monitor what's happening inside the team. Every time we're planning a sprint, there's a chance we'll overcommit again—this is normal. It's our habit!

On the other hand, it makes sense to create a skill matrix and check how the team feels about the learning.

Conclusion

Applying elastic leadership is easier said than done. The concepts and plan are simple, but it involves doing a lot of hard work and stepping out of our comfort zone. In particular, it's tough to have difficult conversations, but once you're out of survival mode, things become easier and more enjoyable.

Once you're entering learning mode, you need to constantly monitor how the team is doing and remind them (and yourself) why you do what you do.

I'll probably write more on the learning mode in the future. I hope this article was helpful! If you're interested in having a chat, why not contact me?